Georgia

I had planned my journey to Georgia mainly out of geopolitical interest. After visiting Ukraine in February 2024 and Moldova in April 2023, I felt compelled to visit the third country with Russian-occupied territory. With the Russian-backed separatist regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, roughly 20% of Georgia’s territory has been under Russian influence since 2008.

I booked an apartment in the center of the capital, Tbilisi, for the full eight nights because I hadn’t yet figured out which parts of Georgia I could—or wanted—to visit. I arrived in the dark, and a Bolt Tesla quickly brought me to the “Old Town” of Tbilisi. According to Booking.com, my apartment had a synagogue view, which was almost true.

Ovanes Tumaniani St, Tbilisi

The back of the Great Synagogue.

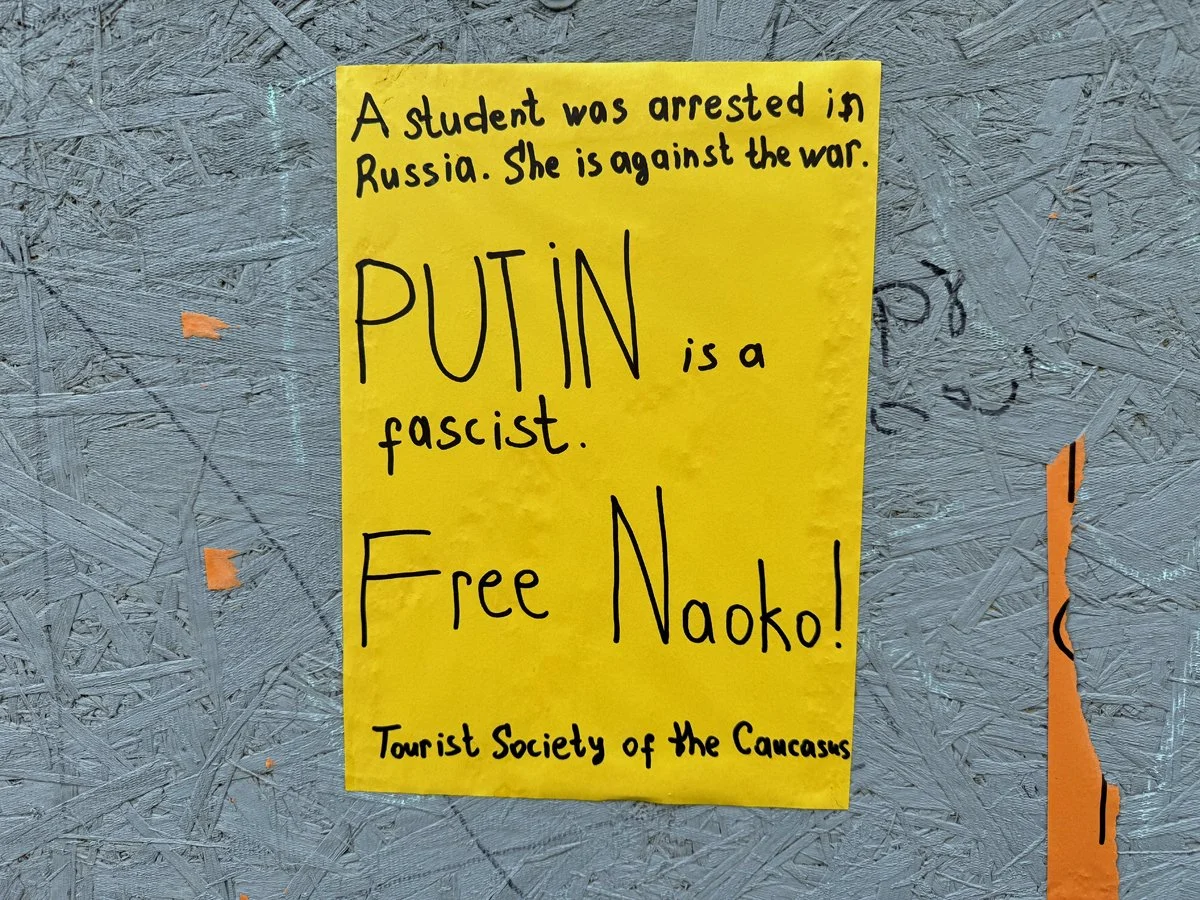

Day 353 of uninterrupted protests in Georgia

I was really in a hurry to join the daily protests. I dropped my bag, unwisely skipped dinner, and walked toward Rustaveli Avenue. People were already gathering, waving Georgian, Ukrainian, US, and EU flags. A few dozen police officers were blocking Rustaveli Avenue. The night before, protesters had wandered onto the avenue and blocked traffic.

The protests were a direct result of the 2024 elections. On 28 October 2024, after the preliminary official results were released, the ruling Georgian Dream party declared victory. That same night, a large crowd assembled, accusing the government of election fraud. Ballot stuffing, multiple voting, widespread voter bribery, intimidation, and voter control were documented by the local watchdog ISFED. The OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) stated: “On election day, frequent compromises to the secrecy of the vote, several procedural inconsistencies, and reports of pressure and intimidation, including through the recording of the process, negatively impacted public trust in the process and an otherwise generally procedurally orderly election day.” [source]

On 28 November 2024, the European Parliament adopted a resolution that explicitly rejected the outcome of the 26 October elections and called for new elections within a year. That obviously didn’t happen. The people of Tbilisi have been protesting in large crowds every single night since 8 October 2024.

But even before the elections, tensions were already brewing. In the spring of 2024, the Russian-style “foreign agents” law was passed. The law requires media outlets, NGOs, and civil society organizations to register as “organizations pursuing the interests of a foreign power” if more than 20% of their funding comes from abroad. Registered organizations must then publicly label themselves as “foreign agents.”

I had skipped breakfast in anticipation of the lunch served during the flight. That lunch turned out to be little more than a bread roll with a sliver of ham. After an hour at the protest, I was too hungry to keep hanging around. The day was almost turning into a one-day fast, and I began to feel dizzy.

Sunday 16 November

I had reserved the first day to explore a city I knew almost nothing about. It was autumn, yet midday temperatures reached a balmy 20 degrees Celsius.

At first, the city confused me. The architecture felt unfamiliar. The UNESCO World Heritage Convention refers to a unique “Tbilisian spirit.” Situated on historic Silk Road trade routes between Europe and Asia, Tbilisi’s historic center is a visual record of those who passed through or ruled it. The local Georgian character is visible in native masonry, wooden construction, and the social culture of balconies and courtyards. The sulphur baths reveal strong Sasanian and Persian bathhouse traditions. Ottoman dominance influenced both the street layout and the wooden house culture. From the early 1800s onward, as Tbilisi became a key city of the Russian Empire, it absorbed Russian provincial classicism, followed later by neoclassical boulevards and Art Nouveau mansions.

In the afternoon, I hiked up to Mtatsminda Park. On the very first day, I realized how hilly Tbilisi is—and how little mountain walking I’d done in recent years, having spent almost every weekend at my parents’ place since 2018. Could I turn my city trip into a mountain hiking vacation?

The hike took about an hour and consisted mostly of stairs. The Tbilisi TV Broadcasting Tower is also located on Mount Mtatsminda. Built in 1972, the entire structure is rusty, but it is also an intriguing feat of mid-Soviet-era engineering.

With a great view over the city, a restaurant is located on the mountain. The Funicular Complex building dates back to 1938. I ordered shkmeruli (შქმერული), chicken and liver cooked in milk (or sour cream) and garlic—a dish from Georgia’s Racha region. I also had my first glass of Georgian wine, a full-bodied white that paired perfectly with the shkmeruli.

A street cat begged for a piece of liver. I pretended to have a heart of stone, but in the end I gave the poor cat some.

Monday 17 November: Stalin Museum

On the second day, I felt restless—I had to see what lay beyond the city. Nothing seemed easier than visiting the Stalin Museum in Gori. Minibuses run between Tbilisi and Gori, but I much preferred the fixed schedule of the train, even though only two trains a day serve the route. One departed conveniently at 8:20 a.m. The fare was 11 lari (€3.50) for the one-hour journey.

Judging by the overpass, it was clear that not much money has gone into the Georgian railways. The VL10 two-unit locomotive (not my train to Gori) was built in Tbilisi, but in its blue livery it belongs to the Armenian railways.

Gori’s Soviet classicist–style railway station is a 15-minute walk from the city center, on the other side of the Mtkvari River. The current building was likely constructed in 1953, while the railway line itself was established in the early 1870s.

There are plenty of modern cars and Teslas in Georgia. Many are imported second-hand, often directly from left-hand-drive countries. Old Soviet-era vehicles are becoming increasingly rare.

Before the Stalin Museum opened in 1957, the house in which Joseph Stalin was born had already been converted into a memorial museum in 1937, during Stalin’s own lifetime. The tiny house was not accessible to visitors when I was there.

In 2025, the Stalin Museum feels like an anachronism. It should either have been dismantled or fundamentally reworked to focus on the brutal years of Stalin’s rule (1924–1953). At 24, he appeared as a strikingly handsome revolutionary; by the time of his death, Stalin was responsible for an estimated 10 to 20 million deaths. These include the Holodomor famine in Ukraine, famines in Kazakhstan and Russia, the Great Terror (1936–1938), the Gulag system, the mass deportations of Chechens, Crimean Tatars, Volga Germans, and others, as well as World War II–related repression.

Stalin statue by sculptor Silovan Kakabadze.

“Out of the protest against jeering regime and Jesuitical methods existed in the seminary I was ready to become and I have really become a revolutionary.”

Since the 2010s, there has been a “Stalin revival” in Georgia, especially among generations who remember the Soviet era. Despite the brutal reality of his totalitarian regime, some Georgians view the “local hero” Stalin as having done much good for the country. This perception is often intertwined with a desire for national pride and a deflection of present-day economic hardship—summed up in the sentiment that “in Soviet times, we had it better.”

Not a painting, but silk embroidery.

The 50+50=120-graffiti might be completely unrelated to the denial of reality by the Party in George Orwell’s 1984 but I immediately had to think of this book.

“In the end the Party would announce that two and two made five, and you would have to believe it. It was inevitable that they should make that claim sooner or later: the logic of their position demanded it. ”

“Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.”

Brotherhood

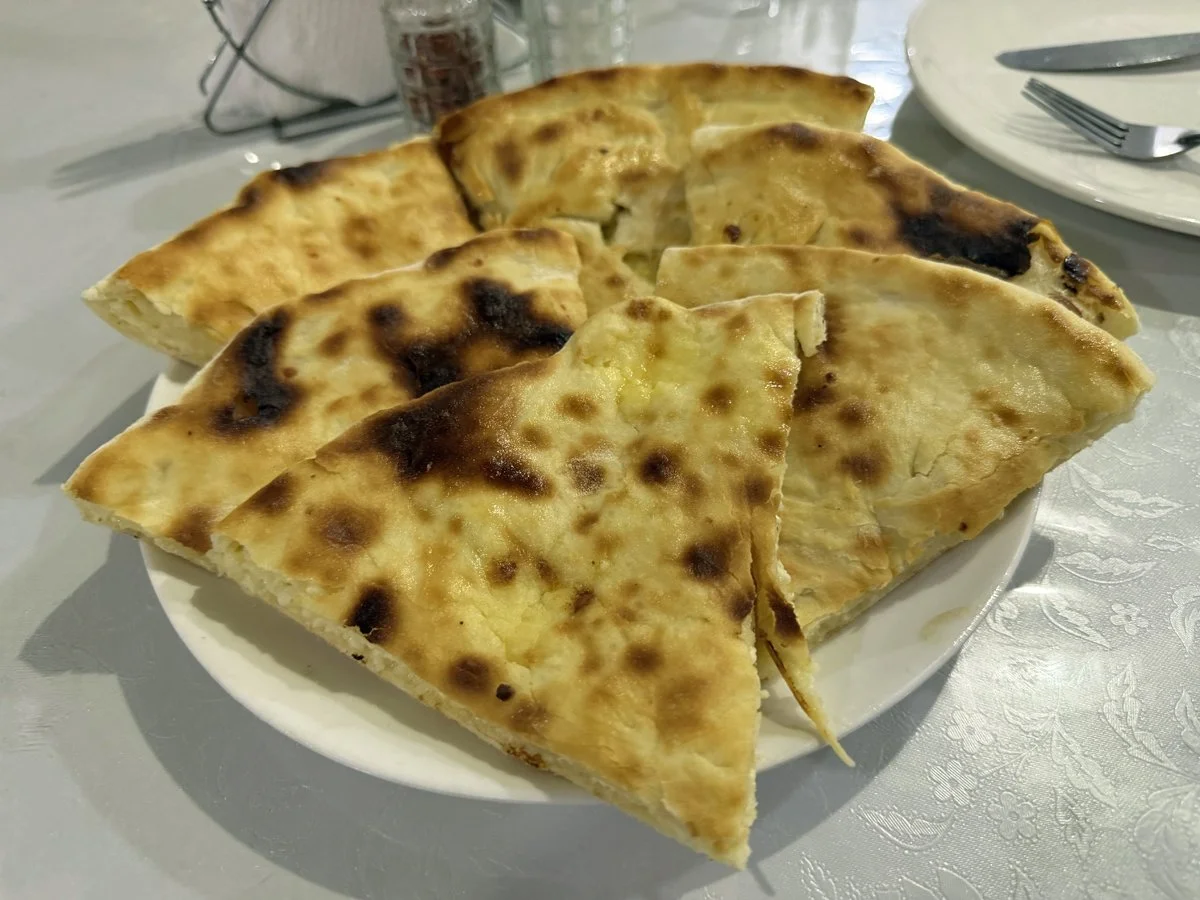

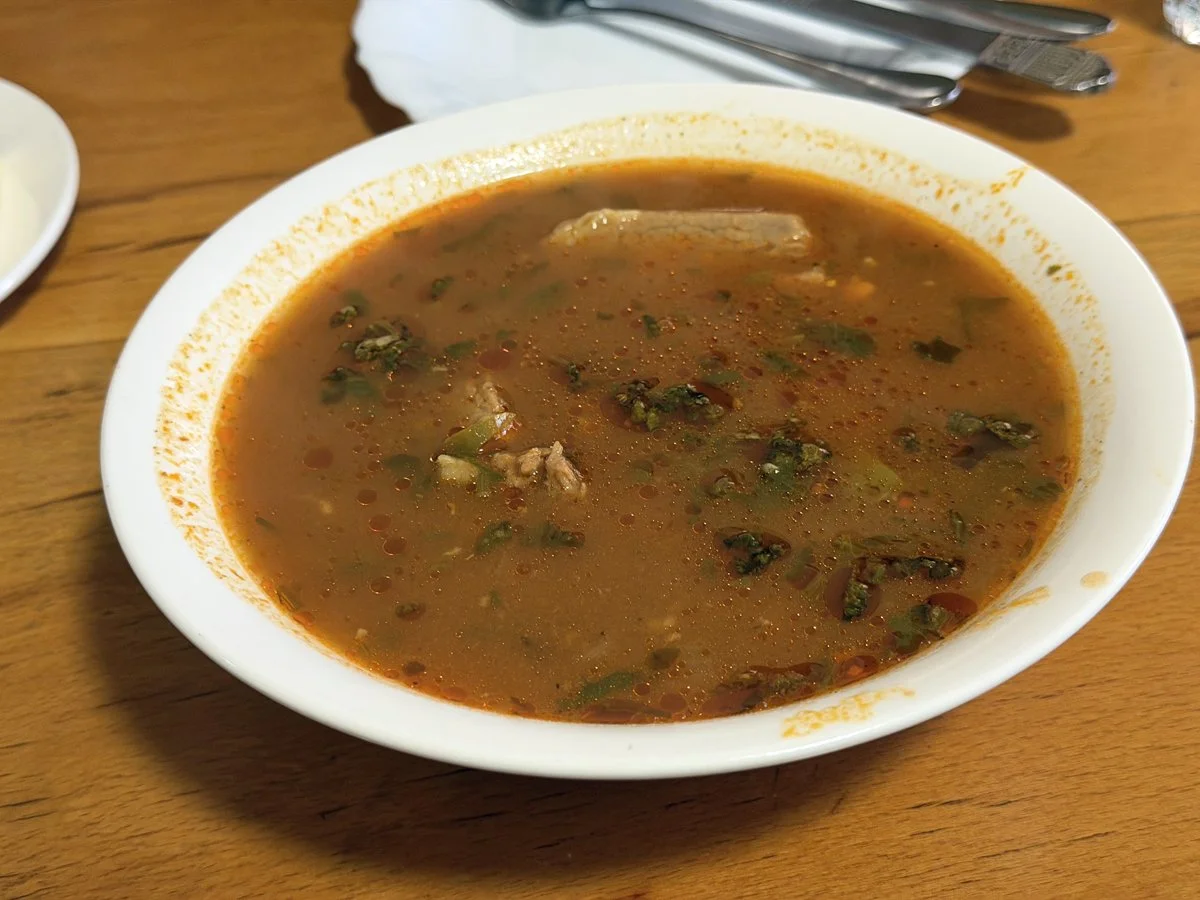

K. Tsamebuli Street, Gori. I was happy to find a traditional restaurant in Gori: the Brotherhood. I ordered chakapuli with veal and a glass of wine, which turned out to be filled right to the rim.

Chakapuli with veal and plenty of tarragon.

Back in Tbilisi, I found my way to a small restaurant that was said to serve excellent khinkali—dumplings filled with meat, usually pork or beef, and sometimes lamb or cheese. Inside each dumpling is a spoonful of broth, so you have to eat them carefully: take a small bite first and suck out the broth before taking a second bite, otherwise it will spill everywhere.

Khinkali alone didn’t seem quite enough for dinner, so I ordered khashlama, assuming there would be some vegetables involved. Instead, it turned out to be just boiled pieces of meat—very tasty, though.

Khashlama (ხაშლამა): boiled beef.

Khinkali (Georgian: ხინკალი))

Next post: Hummus and sulphur baths